Cindy Blackstock was awarded the second annual Janusz Korczak Medal for Children’s Rights Advocacy at a moving ceremony organized in her honour by the BC Representative for Children and Youth office and the Janusz Korczak Association of Canada. The medal was awarded for Cindy’s outstanding contributions towards improving children’s rights in ways that encourage love for children, listening to children, fostering healthy children’s lives, and building capacities in children, in the spirit of Doctor Korczak.

The official part started with the introductions by Jeff Rud, the executive director for the Office of the Representative. Lillian Boraks-Nemetz, an author and a board member of JKAC, painted a very emotional portrait of Dr. Korczak to the assembled audience. Her talk was followed by the presentation of Cindy’s outstanding achievements by Marvin Bernstein, Chief Policy Adviser, UNICEF Canada and Bernard Richard, the BC Representative for Children and Youth. The medal was presented by Jerry Nussbaum, the president of the Janusz Korczak Association of Canada and Bernard Richard. The ceremony was concluded by Cindy Blackstock, who shared with the audience some key moments in her fight for the rights of the First Nations children. Please see below the selected presentations.

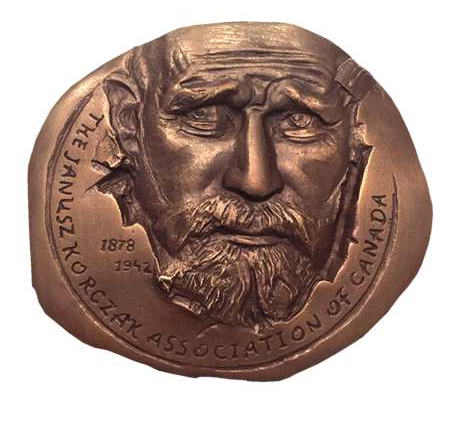

Presenting the Medal (from left to right): Bernard Richard, Cindy Blackstock and Jerry Nussbaum

Representative for Children and Youth press release.

Jewish Independent article.

The presentation by Lillian Boraks-Nemetz

Ladies and Gentleman, Good Afternoon,

It is a great honor to be here today on behalf of the Janusz Korczak Association of Canada and participating in the Janusz Korczak medal award ceremonies.

We have accomplished much in the past few years in the area of child advocacy.

We have published three or four books related to Janusz Korczak pedagogy. For more information on this please got to our website, Janusz Korczak.ca

Among our many activities, we hold at least 3 or 4 annual events:

- The Korczak medal award for child advocacy such as this afternoon.

- We hold a program jointly with UBC -Dean’s Distinguished Speaker’s Lecture

- We offer a scholarship to a graduate student researching topics on children’s rights.

- Also a Korczak statuette award to a distinguished pediatrician or social worker, or someone in Social Pediatrics.

Last year we co- sponsored with University of British Columbia’s Department of Education, 6 lectures which touched on various facets based on Korczak’s noted book on How to Love a Child. These included 30 panelists from various walks of life.

And now a word about this great man whose light still illuminates the path for those who love and care about children. First and foremost Korczak whose real name is Henryk Goldszmit was a children’s advocate, their doctor, their friend and teacher. He penned his own index of children’s rights which is reflected in the United Nations Charter.

Dr. Korczak seemed to know the mind workings of a child, his needs his foibles his sadnesses and joys. His Warsaw Ghetto diary and other writings inform us on how he through self-examination and experience became a man with deep concern and compassion for a child’s welfare. A child’s healing not only of the body but also of the mind.

I found the following quote in Betty Lifton’s book: From How to Love a Child written by Korczak and I quote:

“The child- a skilled actor with a hundred masks a different one for his mother, his father, grandmother or grandfather; for a stern or lenient teacher, for the cook or maid, for his own friends for the rich and poor. Naive and cunning, humble and haughty, gentle and vengeful, well behaved and willful, he disguises himself so well that he can lead us by the nose.”

In general, Korczak was a man who wore many masks himself but as the saying goes, all roads lead to Rome, his many masks had at their core the welfare of children. Indeed, Korczak must have been aware of his own inner child and that is how he knew about other children.

He went beyond his specialization as a pediatrician and reached out to other areas of a child’s human need.

As for his masks: He was a doctor who listened with all his senses to the child. He was the kind of a listener who really heard the child and gave him opportunities to speak out.

He was a teacher who taught without appearing to be teaching, the best kind of teacher who involves the student and interacts with him or her. Thus he was more than a teacher but also an educator who enriched a child’s emotional and intellectual development in relation to his environment, culture and religion.

He was a mother and father to the orphans, caring for them and loving them; a psychologist who intuited and was interested in how a child’s mind works, the child’s thoughts and feelings.

He was a social reformer and a bread winner.

Korczak was an author whose many books were dedicated to children and were about children.

His roles one might say all fit under the umbrella of Korczak as a philosopher whose theories he set to practice and which are now taking root in this country and even globally.

Korczak ran his Orphan’s Home as his microcosmic laboratory where he practiced and researched his philosophy on How to Love a Child, and on children’s rights. There, he conducted a child’s court where Children expressed their grievances in front of the judges and Jury made up of children.

When my children were small I adopted this method partially and invited my own children to the family room once week where they would express their grievances to us their parents. We would hear them out and we’d discuss solutions to all sorts of problems. And this worked very well as the children needed to gain confidence in themselves and to express their feelings and thoughts, to be treated fairly with an acknowledgement of their rights to justice.

We need more Korczaks particularly in our troubled world where children suffer abuse, hunger and other atrocities. And that is why we cannot emphasize enough the goodness of the work that is being done today by all those who plead and work for children’s rights. Their freedom to be who they are meant to be and above all their right to live and to live in peace and freedom.

Korczak wrote the following words:

in his book on How to Love a Child and I quote again:

One hundred children are one hundred human beings. Not “someday,” not “not yet,” not “tomorrow” — they are human beings now.

In 1942 Korczak became a hero.

He would not desert the 200 hundred orphans he cared for in the Warsaw Ghetto at the time when the orphanage was marked for Nazi deportations of Jews. At the Umschlagpltz station where the trains destined for Treblinka stood waiting Korczak was offered a reprieve from being deported, but he said “My children need me” and went with them to Treblinka death camp where they all perished.

Irena Sendler, a Polish woman with a heart, herself a rescuer of the ghetto children said the following: and I quote

………”when on August 6, 1942, I saw that tragic parade in the street, those innocent children walking obediently in the procession of death and listening to the doctor’s optimistic words, I do not know why for me and for all the other eyewitnesses our hearts did not break.”

In conclusion here is a poem about Korczak’s unforgettable last walk through the streets of the Warsaw ghetto to Umschlagplatz, at the head of the two hundred orphans and the orphanage assistants.

His Last Walk

by Anda Amir

“Where are we going?” the children asked.

He walked ahead of them all,

looking as calm as if he were going

out for a holiday stroll.

“We’re going to be free,” he answered.

“See, the gates are open wide.

Don’t cry — just sing! It’s a holiday,

and we’re going, we’re going outside!”

And the street unrolled like a carpet

as the barefoot children walked past.

Singing, “We’re going, and not alone,

to the fields, the green fields at last.

“The doctor is with us, he will not leave

his children. We’re going together,

and we know he’ll go with us till the end,

he is with us now and forever.”

Thank You

Presentation by Marvin Bernstein

First of all, I would like to thank Bernard Richard and Jerry Nussbaum for extending an invitation to UNICEF Canada to participate at this exciting event honouring the many contributions of Dr. Cindy Blackstock.

In thinking back over time, I have known Cindy for about 15 years and I can’t think of a more passionate and tireless advocate for the equitable treatment of First Nations children. When I have spoken to Cindy and asked her about how she sustains her energy and resolve through some very dark days, her answer is always the same – “It’s all about the children” – that is where she derives her energy and motivation.

The first time I heard Cindy speak was when I was working at the Ontario Association of Children’s Aid Societies in Toronto. I couldn’t believe the power of her presence and the force of her presentation. To my surprise, she didn’t need notes or a microphone for her voice to fill the room. Her message was simple – it was time to end the systemic discrimination against Canada’s First Nations children and do the right thing. Cindy is clearly one of the great human rights orators of our time. Yet I only recently learned that in university, Cindy avoided all courses that involved public speaking. Now with Cindy’s speaking prowess, who would have guessed that little known fact?

It’s only fitting that Cindy should be receiving this prestigious award that bears the name of Janusz Korczak. Dr. Korczak is an iconic figure, who was aware of the interrelationship between children’s rights and human rights long before there were human rights treaties to tell him so. He was a man of great intellect, courage and compassion. He was also a man of many talents – a paediatrician, author, and philanthropist, who is considered to be the father of children’s rights. It’s incredible to think that close to 100 years ago, he had the wisdom to see things from a child’s perspective and to establish a children’s senate, a children’s newspaper and a children’s court in his Polish orphanage. His goal was not only to support children’s healthy development, but also to respect their fundamental human rights, These rights would form part of a vision that would first find expression after the Second World War in the 1959 Declaration of the Rights of the Child, and eventually in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child itself some thirty years later.

It’s now a full decade since the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada, with Cindy Blackstock as Executive Director, and the Assembly of First Nations co-filed a complaint with the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal alleging that child welfare services provided to First Nations children and families on-reserve were flawed, inequitable and discriminatory. The complaint cited a long-standing pattern of underfunding child welfare services for First Nations children living on reserve, affecting 163,000 First Nations children and families. The complainants asked the Tribunal to find that First Nations children were being discriminated against and order appropriate remedies.

Looking back in time, it was an unprecedented and courageous act on the part of the Caring Society and the Assembly of First Nations to initiate this human rights complaint. By her own admission, Cindy didn’t fully understand how to complete the forms; she had no legal team to assist her at that point. At a press conference convened on February 23, 2007, announcing the filing of this human rights complaint, Cindy Blackstock described the over-representation of First Nations children in child welfare care as “drastic”, while remarking that “after ten years of research and negotiation and numerous independent reports” consistently demonstrating “the inadequacies of the federal funding formula and its negative impacts on First Nations children”, it isn’t possible to “wait any longer for the federal government to do the right thing.”

After many false starts and almost 9 years later, on January 26, 2016, the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal finally issued its ruling relating to the human rights complaint. It found that First Nations children and families living on reserve were discriminated against in the provision of child and family services on the basis of race and national ethnic origin. In particular, the Tribunal held that Canada’s discriminatory conduct “incentivizes” the removal of First Nations children from their families and communities. The Tribunal also found that Canada’s failure to fully implement Jordan’s Principle amounted to racial discrimination.

It is clear to us at UNICEF Canada that Cindy has been on the right side of history from the very beginning and has left an enduring legacy of advancing First Nations children’s rights. From a child rights point of view, First Nations children should be treated fairly and equitably in the funding and delivery of all services on reserve; they should not be treated like second-class citizens and receive less funding and services than all other Canadian children. They should be able to exercise their full constellation of rights under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, including their right to non-discrimination; to have their best interests treated as a primary consideration in all decisions affecting them; to assert their right to life, survival and optimal development; and their right to enjoy and fully participate in their own culture and language.

Having ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child, the government of Canada has an obligation to ensure that the laws, policies, funding, and services which provide for these rights, do so equitably. In December 2012, this point was made clear by the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child, when it expressed concern regarding the “significant overrepresentation of Aboriginal children in out-of-home care” and recommended that Canada “take urgent measures” to address the problem.

Prior to the release of the Committee’s Concluding Observations, I was in Geneva in February of 2012 representing UNICEF Canada at the pre-sessional meeting with the Committee where alternative or shadow reports are presented to the Committee. Cindy was there too and she had the foresight to bring a group of First Nations young people from different parts of the country who could speak to the Committee directly about their own personal experiences. This was not something the Committee had been exposed to in the past and the Committee members were taken aback by the degree of preparation and intelligence exhibited by these remarkable young people. Cindy also brought a film crew from the National Film Board of Canada to capture the journey to Geneva and the unique experiences of these First Nations young people. When the film crew was not permitted to shoot the actual closed session before the Committee, Cindy was able to work around that impediment and have the young people interviewed on film immediately afterwards and at a special reception in Geneva to honour their contributions, that I was fortunate to attend. This was quintessential Cindy Blackstock – breaking the barriers and constantly developing new tactics and strategies in response to changing circumstances and evolving opportunities.

Breaking barriers and using innovative approaches have been two of Cindy’s signature achievements. She is not one to simply rely upon making aspirational statements. She has rallied children and adults alike behind Jordan’s Principle and Shannen’s Dream. She has enlisted tens of thousands of supporters behind her ‘I am a Witness Campaign’ and ‘Have a Heart Day’. Internationally, she has not only made representations to the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, but also to the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, and last December, to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in Washington, D.C. A few years ago, she was instrumental in arranging a visit to Canada by the Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples that resulted in a critical report regarding the state of Indigenous rights in Canada.

From UNICEF Canada’s point of view, it is important to realize that when First Nations and other children are left behind, this isn’t simply a concern limited to those communities. Allowing wide gaps between children in different aspects of their well-being is costly not only to the children left behind, but to all children in our society. UNICEF’s research on child well-being across affluent countries shows that countries with the best outcomes for all children have the smallest gaps between them. In UNICEF’s Report Card 13 released in 2016, Canada slipped to the back of the pack, ranking 26th of 35 affluent nations, when compared on an index of inequality in child well-being, measuring the gap between children in the bottom 10 percent with children at the median across four key domains of child well-being: income, education, health and life satisfaction.

We have arrived at a crossroads in time, where our federal government must take active steps to ensure that our First Nations children are not relegated to second-class status, and can exercise access to the same services – without denial, delay or disruption – as all other children in this country. First Nations children should not be compelled to wait endlessly and suffer multiple disadvantages without appropriate funding and services, while the wheels of litigation grind slowly. As Cindy Blackstock said in that early press conference on February 23, 2007, we have to speak up “for the children” and demonstrate that “we love them enough to stand up for them and give them an equal chance to live safely at home – just like other Canadian children.”

In closing, it’s incredibly heart-warming to see Cindy being recognized for her extraordinary advocacy after many years of resistance by the federal government and so many hardships and distractions thrown in her direction. A weaker individual would have succumbed to these pressures many years ago. Cindy has shown immense resolve and has never given up hope that things could change. While Cindy has always been there to prop up her supporters and other child-rights advocates, she has never asked others to do anything for herself on a personal level – it has always been about the children. As John Milloy, a Canadian historian and professor at Trent University, has aptly stated: “We all leave legacies, but not all are of equal weight.” In the case of Cindy Blackstock, we are blessed to see a growing legacy of enormous proportions that will dramatically change the life conditions of First Nations children, families and communities for generations to come.

CONGRATULATIONS CINDY ON THIS WELL-DESERVED AWARD!

Presentation by Bernard Richard

A comparison: Janusz Korczak and Cindy Blackstock

You may think that it would be difficult to make comparisons between a Polish Jewish man who died in the Holocaust and an Indigenous Canadian woman who is still living.

But Cindy Blackstock is being given this Medal for Children’s Rights Advocacy because her work – and her life – has embodied the spirit of the man for whom the medal is named.

I know it is customary to say this I truly believe this to be the case: I can’t think of anyone more deserving of this honour than Cindy Blackstock.

Firstly, she made sure to tell us that “the award is dedicated to all First Nations children, youth and their families and the allies who stand with them in their pursuit of justice, equity and reconciliation. Justice will win and when it does – the country will too”.

Cindy Blackstock, a member of the Gitksan First Nation, is the Executive Director of the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada and a Professor at the School of Social Work at McGill University. Using a multi-disciplinary approach embedded in principles of reconciliation she works with First Nations communities to educate, and engage, all Canadians to address the cross-cutting inequalities affecting First Nations children and their families. She is currently serving as a Commissioner for the Pan American Health Commission on Health Equity and Inequity.

As many of you already know, Janusz Korczak was a pioneer in child advocacy … and a worldwide symbol of commitment to the rights and well-being of children and youth.

He was a pediatrician, researcher, writer, advocate for children’s rights and an officer in the army … but most of all, he was an educator and a “moral authority.”

Cindy is also a moral authority.

She has spoken out about the systemic inequalities in public services experienced by Indigenous children, youth and families throughout her working life.

Her more than 25 years of social work experience in child protection and Indigenous children’s rights exemplify what it means to dedicate one’s life to vulnerable children and families.

And like Korczak, Cindy is a prolific writer, with more than 50 publications to her name.

Cindy Blackstock and Janusz Korczak have both been recognized around the world for their work …

In Cindy’s case, she has been recognized by the Nobel Women’s Initiative, the Aboriginal Achievement Foundation, Frontline Defenders and many others for her promotion of culturally based equity for First Nations children and families and engaging children in reconciliation.

The human rights complaint that Cindy and the First Nations Child and Family Caring Society launched in 2007 … took nine long years until the landmark CHRT ruling in January 2016.

Time and again, Cindy fought back against a much stronger adversary – the government of Canada.

She was tenacious and persistent. Determined, passionate and committed … all characteristics shared with Janusz Korczak.

From the time, several years ago, when I had the opportunity to attend the play “The Children’s Republic” based on Korczak’s life and work, he has stood out as a giant in the area of children’s rights.

From the first time I met Cindy Blackstock, she has left the same indelible impression.

They deserve to be mentioned in the same breath and with the same admiration.

And they have each set aside their own personal gain for one goal: the advancement of the human rights of children.

I am so honoured to be able to participate, with all of you, in saluting this remarkable human being, Cindy Blackstock.

Cindy Blackstock

Lillian Boraks-Nemetz

Marvin Bernstein

Presentations

Jerry Nussbaum

Ziba Varghi and Bernard Richard

Bernard Richard