About the book

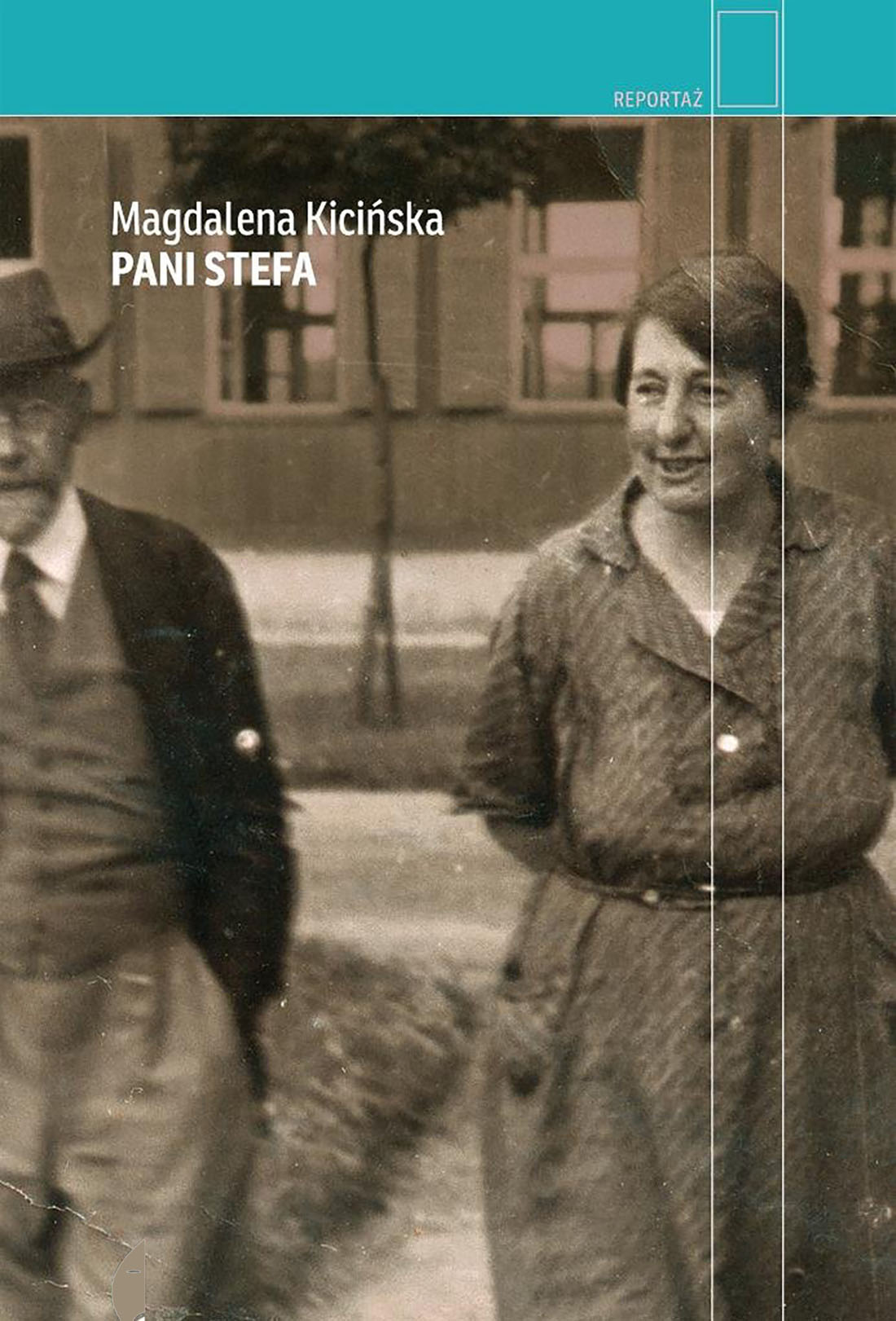

Pani Stefa (Miss Stefa) by Magdalena Kicińska

From the Book Institute Poland http://www.bookinstitute.pl

“I often found myself wondering how she always knew where to be at the right time. Whenever I got up to mischief, she was the first to know about it. And as soon as any of the children started to feel sad, she would instantly ask what was wrong. She’d produce their lost item from a pocket, and a handkerchief too, to wipe away the tears … The way she lived, we knew very little about her, she was so… So… non-existent. There’s nothing left of her, as if she were never here.”

Stefania Wilczyńska was born in 1886 in Warsaw, into an assimilated, well-to-do Jewish family. From 1906 to 1908 she studied natural and medical sciences in Geneva and Liège. She also took courses inspired by the German pedagogue Friedrich Fröbel, designed to train future kindergarten teachers. In 1909 she returned to Warsaw, where she asked for “an unrecompensed position” at the refuge for Jewish children situated at 2 Franciszkańska Street. There she met Dr Henryk Goldschmidt, who often called in there, and who had an interest in various educational methods. At the time he was working as a paediatrician at the Bersohn and Bauman Children’s Hospital, and had started to publish under the pseudonym Janusz Korczak.

Wilczyńska and Korczak had similar views on bringing up children, who deserved respect, trust and freedom, as long as no harm was caused to anybody else. At the children’s home that they ran, there was a set of rules in force which included a code of laws and duties for the staff as well as the children. There was a self-governing body and a court in operation too. Wilczyńska was in charge of keeping order – it was she who made sure the several dozen children had clean clothes without holes in them, were fed a healthy diet, got up early enough to wash and have breakfast before going to school, and then do their lessons, etc.

Those who grew up in her care remember Stefania Wilczyńska as a silent, austere person, always dressed in black, with short black hair and an inseparable bunch of keys. As Samuel Gogol remembered: “I don’t think she was cold. The children’s home couldn’t have existed without this extraordinary lady with the serious face. She took an interest in every little detail. The doctor wasn’t interested in things like our clothes, or whether our hands were clean and we were tidy. I think she substituted as a mother and a father for us, because somebody had to guide us with a firm hand. In my memories the home was Miss Stefa, and Miss Stefa was the home.”

She lived in Korczak’s shadow, and that is where she has remained. Many streets, children’s homes and schools have been named after him, and many monuments have been erected to him. They all show him at the head of a procession of children, apparently on their way to the Umschlagplatz, from where they would be forced into cattle trucks that would take them to the death camp where they would die in a gas chamber. Stefania Wilczyńska is not there with them, though everyone knows that she was. In May 1978, on the grounds of the former camp at Treblinka a stone was ceremonially unveiled to commemorate Janusz Korczak and the children. Among the 17,000 stones that comprise the monument there, it is the only one to have a name carved on it. Why couldn’t they find room to remember Stefania Wilczyńska there too? It’s a mystery.

– Katarzyna Zimmerer

Translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones

*****

The word “pleasure” doesn’t come up when they talk about Stefania Wilczyńska. Pleasure would prompt a smile, and they don’t think that suits her.

“Not that she never smiled,” explains Szlojme. “She did smile occasionally, and she laughed too. But that laughter wasn’t at home with her. In Stefa’s case it was like a guest who’s come from far away and doesn’t know what to do with himself.”

It was strange to see her laugh.

It was good to see her laugh.

“Don’t get us wrong: she had large, deep set eyes, a big nose, wrinkled cheeks, short wisps of hair bordering her face, a little black mole, and a furrowed brow. Tall, stocky, in a black dress. She was always holding that bunch of keys, heavy and jangling.”

Hardly the setting for “pleasure”. But one day Szlojme calls, clearly overjoyed.

“There was something! The microscopes I told you about. One night I saw her taking one upstairs to her room. She gave me an embarrassed look, and from then on we shared a secret.”

She also enjoys offering the children botany textbooks to read with large charts. She likes telling them about Darwin’s discoveries. In 1921 when the “Rosebud” summer camp is set up at Gocławek (then outside Warsaw), she can take the children for walks, show them the meadow, and say: “In the daytime cows graze here” (one little girl by the unusual surname “Krowa”, meaning a cow, is offended: “I’ll take you to court!” she says). So she goes on to explain what a cow is, a river, a forest. Some of them have never seen this many trees before.

Apparently she also likes talking in French, and when she gets upset, she mumbles to herself in it, so the children won’t understand.

(Is that when she’s planning expenses, and can see the funding from the Town Hall dwindling?)

In the early 1920s the “Aid for Orphans” Society asks the city authorities for help; it doesn’t want to keep going on nothing but donations and the good will of the donors. It is looking for new ways to raise money. Other institutions will pay to make use of the summer camp. On an extra piece of hired ground they found an agricultural farm. A few years later a boarding house will be established there for children waiting for a place at the Home, and for those who are behind with their studies, and in 1928 a pre-school too (which will be run by boarding house resident Ida Merżan).

(Does Wilczyńska add reminders to her plan for the day, saying: pre-school inspection, answering young employees’ questions, time to send hundreds of children to “Rosebud” in the summer, divide them into groups, equip and travel with them?)

At first the children cannot cope, away from Krochmalna Street. As Icek Cukierman, brought up at the Orphans’ Home, and later transferred to Gocławek, remembered: “The only thing that connected us with the Orphans’ Home were Miss Stefa’s weekly visits, which I looked forward to impatiently.”

*

According to Szlojme: “She demanded a lot of everyone, and the most of all of herself.”

Sara Kramer, another Orphans’ Home foster child, remembered: “I missed my mum very badly. I went to visit her on Saturdays, and it was very hard for me to go back to the Home afterwards. My mum was always my mum, but if I had stayed with her, my life would have been very different. I wouldn’t have got from her what I got from Stefa.”

Hanna Dembińska lived in the Home too. “Whatever she did for me, she wasn’t my mother. I think she envied her,” she said of Stefa.

According to Seweryn Nutkiewicz: “Korczak and Stefa were less than parents, and more than parents. They were our foster parents. […] A father views his child subjectively, […] a foster father does it objectively. They guided us, not from the start and not to the end. In the family a child comes up against real life on a daily basis. The Home on Krochmalna Street was a closed world.”

An anonymous memory: “Korczak appears briefly, and the children run to him with their concerns, they drag him into their games, and he doesn’t refuse. Stefa was the mother of the home, often strict by necessity, and it’s not hard to understand that out of 107 children in her care, some might have grudges towards her. She was tough, and sometimes she punished someone for nothing. They gave us warmth, but it was a foster parent’s warmth, only a foster parent’s. But anyone can be a father or mother. Only very few are capable of raising other people’s children.”

As Ida Merżan remembered: “Once I was asked how many children Miss Stefa had, so I said for a joke: fifty girls, fifty boys, twenty at the boarding school, and one older child, the most difficult of all, because he’s independent – Korczak.”

Jochewed Cuk: “Korczak was the kind dad, and Stefa was the tough mother, always there, twenty-four hours a day.”

Samuel Gogol: “I don’t think she was cold. The Home couldn’t have existed without this extraordinary lady with the serious face. She took an interest in every detail. The doctor wasn’t interested in things like our clothes, or whether our hands were clean and we were tidy. I think she substituted as a mother and a father for us, because somebody had to guide us with a firm hand. In my memories the home was Miss Stefa, and Miss Stefa was the home. … As for financial matters, it was mainly she who took care of them. The person who made sure I had a pair of trousers and put on my slippers was Miss Stefa. Nobody ever talked about it – it was self-evident.”

*

In Ada Poznańska-Hagari’s anonymous questionnaire of the 1980s they also said:

“She was like a mother, but the kind that holds you tight.”

“She could shout at a child so sternly he was terrified.”

“As a child I thought the Doctor was better, but looking back I think Stefa’s part in my upbringing was no less important.”

“The Doctor was more sensitive and affectionate. She had to be tough.”

“Korczak was like a mother, and Stefa was the father.”

“When she was cross with me, she wouldn’t talk to me or answer me. I realized she was cross, but I didn’t know why.”

“When the girls started having periods, she took special care of them. She let them have an extra bath. She would have a talk with them. I was embarrassed. She explained to me exactly what was happening.”

“There were children she didn’t like. She threw me out of the Home for nothing.”

“Why did she love me so much? I was awful.”

“When I turned seven, she held a birthday party for me, although there was no such custom at the Home. She asked who I liked, and invited those children. There were snacks and songs. I had a wonderful birthday.”

“We’d been ill and we were lying in our beds. Korczak examined us and confirmed that we were better now. We stayed in bed, waiting for Miss Stefa to come back and say we could get up.”

“I was meeting a boy in secret. Stefa came in and put on the light. Afterwards she came in every night to check that I was in bed. If Stefa was like a mother, then why didn’t she trust me?”

“She said: ‘I know there’s something wrong with this method. Direct communication with a child is better.’ But she didn’t change it.”

“Once she slapped my cheek, I can’t remember why. We were on our own. I said: ‘I’ve got hands too and I can slap you back.’ She stared in amazement and – hugged me. She didn’t apologise, but she hugged me, knowing she’d made a mistake.”

“There was no arguing with her.”

“I didn’t like her.”

“I loved her.”

*

[…]

This is a letter dating from the late 1930s, which Wilczyńska wrote to a former, now adult foster child (whose surname has not survived):

“My dearest child, I won’t try to console you or reason with you. The fact that Julek shares your feelings and that others sympathise won’t be any help to you either. Nobody and nothing can provide comfort in a situation like this. Only time and work will do their job. We can see this all around us in the example of other people who have been through similar losses. I know it from my own experience of escorting various loved ones to the graveyard.

Other people can’t help at all. Each of us is alone with our own pain. Nobody can take it away for us, nobody can provide comfort, not even the most loving person.

What I’m telling you is tough, my dearest child, but it’s the truth. Not even the thought that one day you’ll have another child, not even that will be any consolation for you right now.

The one good thing is that you have a man like Julek by your side, and he has you.

I’m longing to see you, but I don’t really know when that will be. …

I hug you and kiss you, just like when you were a little girl and something had upset you.”

- Translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones

Reviews

It is hard to believe that for so many years the role of Stefania Wilczyńska was reduced to the role of helpers Janusz Korczak. What is unfair to a woman without whom the Warsaw Orphanage at Krochmalna could certainly not exist. And how well that Magdalena Kicińska pulls Ms. Stefa out of the shadows, restores her dignity and the same place next to Mr. Doctor.

Magdalena Grzebałkowska