About the book

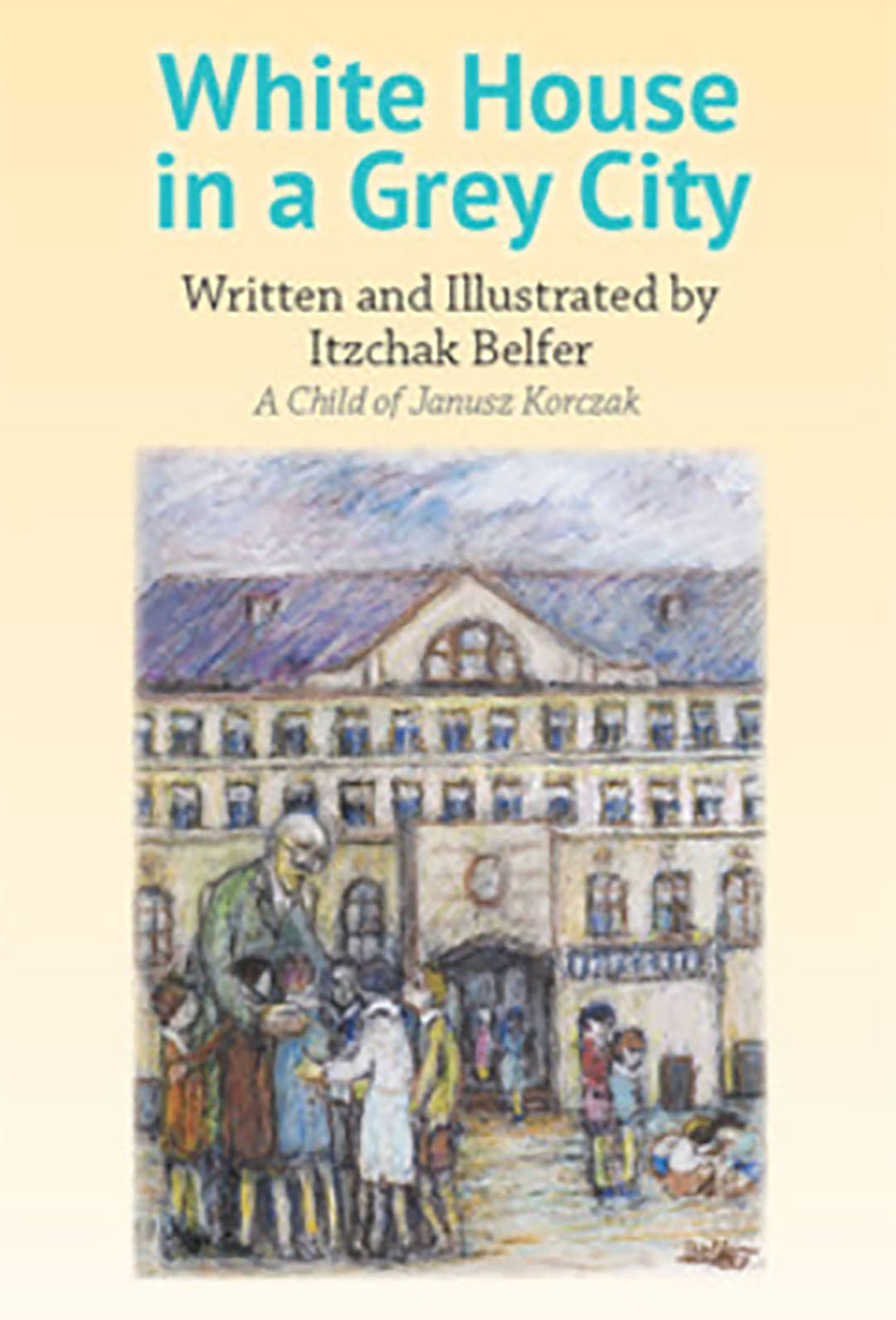

An English translation of excerpts from the book by Itzchak Belfer has been published by the Advocate for Children and Youth of Ontario in cooperation with the Janusz Korczak Association of Canada. The book, White House in a Grey City was launched on April 6, 2016 as a part of the 6th session in the How to Love a Child, the Janusz Korczak Lecture Series at the University of British Columbia.

The book consists of the first four chapters of the original Hebrew edition, as well as a collection of paintings by Itzchak Belfer. These chapters tell us a compelling story of Itzchak's years as a child of Janusz Korczak at the orphanage "Dom Sierot". Translated from the Hebrew by Ora Baumgarten.

Reviews

This portrayal of a Jewish child’s life in the 1920s and 30s in Warsaw is a very moving and detailed autobiography by a gifted writer and artist who grew up in the orphanage run by Janusz Korczak and his colleagues and includes many pictures he drew of the orphanage and its inhabitants.

“White House in a Grey City” is an apt title for a very special book, describing what an extraordinary place the author grew up in and how Korczak and his staff created an oasis of hope for the children in their care in the midst of suffering. In it Belfer connects us with his own past some 80 to 90 years ago. He starts at his own home with his mother and grandparents in Warsaw after his father had died when Belfer was very young. This left his mother alone with six children, all of whom were still at home at the time. He goes on to describe how he was taken into the Jewish orphanage at Krochmalna 92 when he was almost seven years old. Belfer’s initial meeting with Korczak on that first day is clearly etched in his memory and is most lovingly described.

There are also rich descriptions of the children’s lives at the orphanage and of the roles of Korczak and his close colleague Miss Stefa and the other staff. Korczak believed that children should be recognized as full human beings and treated with respect, which was at odds with the prevailing beliefs of the time and progressive even by modern standards.

Belfer outlines the workings of the Children’s Court that offered all the inhabitants of the orphanage a chance to seek justice for perceived wrongs done to them, including the right for a child to accuse an adult of mistreating him or her, an almost unheard of concept at that time or indeed today.

He also talks about the way his artistic abilities were recognized and nurtured in the orphanage, by direct encouragement from Korczak and Miss Stefa and the provision of materials and a quiet space for him to paint and draw. Clearly Korczak and his staff intended to help each child realize their full potential in life. There was also a sustained opportunity for ongoing contact after they left the orphanage at 14 or 15, with regularly scheduled visits from former orphans which over time came to include their spouses and their own children.

Korczak also helped Itzchak overcome a serious stutter and protected him at school from being forced to make presentations to the class that would have set him up for ridicule by his peers. This attention to the detailed needs of each child is one of the impressive aspects of Korczak’s child care model, though I hasten to add it seems sad to recognize how unusual this was, both then and now, to show such care for the individual orphaned or abandoned child’s needs.

Besides running the orphanage Belfer describes how busy Korczak was due to his involvement in many other activities. These included writing books both for and about children, appearing in the courts on behalf of delinquent youth and running a children’s section of a national newspaper with a staff of writers and editors, all children themselves, all over Poland. In addition Korczak lectured on children’s needs at the medical school and he and Miss Stefa ran a training program for the younger staff at the orphanage. Finally there was a second such orphanage for Catholic children that Korczak also oversaw.

Graduates of Korczak’s orphanages went on to become leaders in their communities, many moved to Palestine and helped build the Kibbutz movement and some became ministers in the Polish government. Tragically Belfer was the only survivor if his family during the Holocaust, having gained his mother and Korczak’s blessing to flee Warsaw for the Soviet Union after the Nazi invasion of Poland. The children living in the orphanage when the war started continued to be protected by Korczak in the Warsaw Ghetto until August 1942 when 192 children were sent in cattle trucks to Treblinka, along with Korczak and the rest of his staff and murdered there. Belfer has dedicated much of his life as an artist to commemorating his mentor Korczak and the children.