The Janusz Korczak Association of Canada is honoured to announce the 2022 laureates of the Janusz Korczak Awards in Child Advocacy:

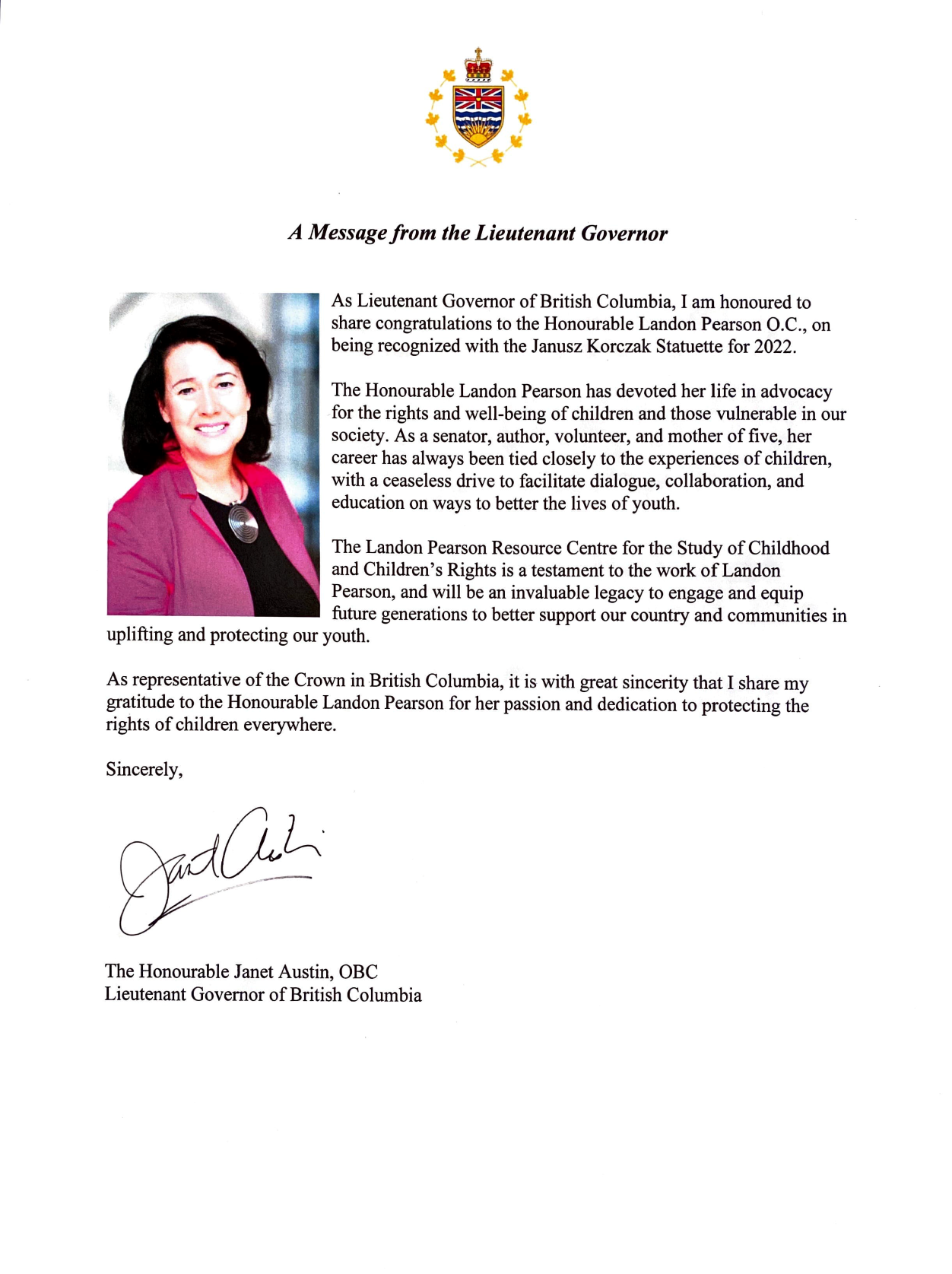

Hon. Landon Pearson O.C. is awarded the Janusz Korczak Statuette, under the distinguished patronage of Her Honour Janet Austin, Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia

Adrienne Montani is awarded the Janusz Korczak Medal, presented in partnership between the Janusz Korczak Association of Canada and the British Columbia Representative for Children and Youth

The Zoom Ceremony honouring the distinguished award recipients took place on October 18th, 2022.

View the Program Brochure here.

View the video recording of the Ceremony here. (For the transcript of the Introduction to Janusz Korczak, please see below.)

Keynote Speaker Dr. Jennifer Charlesworth

Dr. Jennifer Charlesworth is British Columbia’s Representative for Children and Youth, appointed in 2018. She has worked in the B.C. social and health care sectors since 1977, and her experience includes front-line child welfare, social policy, program management and executive roles within government and the non-profit sector, teaching child and youth care at the University of Victoria, and has served on numerous community board and provincial advisory committees.

She was engaged in formative work on deinstitutionalization, community inclusion for people with disabilities, women’s and girls’ health, mental health and youth services. Some of Dr. Charlesworth’s non-profit work has included working with Indigenous organizations to co-create new ways to support Indigenous children, youth and families, as well as being immersed in developing the leadership, innovation and cultural awareness of the community-based social care sector.

Dr. Charlesworth lives in the traditional territories of the Lekwungen and WSÁNEĆ peoples. She has a PhD in Child and Youth Care from the University of Victoria, and an MBA from Oxford Brookes University in Oxford, England. She is an award-winning teacher, author, activist and a parent of two vibrant young women who remind her daily of the power and promise of young people.

Medal Recipient Adrienne Montani

Adrienne Montani is the Executive Director of the First Call Child and Youth Advocacy Society, where she has worked for over 20 years. Prior to working with First Call, she served as the Child and Youth Advocate for the City of Vancouver, and as the chairperson of the Vancouver School Board for three of her six years as an elected school trustee. Some of her earlier leadership positions included serving as the executive director of Surrey Delta Immigrant Services Society and of Big Sisters of BC Lower Mainland.

Adrienne has a long-standing commitment to the issues of cross-cultural awareness and racism, women’s and children’s rights and the impacts of social exclusion on children and youth in low-income families. Her academic background is in Asian studies and adult education.

Adrienne’s work for BC’s children and youth has been acknowledged by a number of organizations: The British Columbia Medal of Good Citizenship, the Bill McFarland Award for the Excellence in the Advancement of Child Welfare from the Parent Support Services Society of BC, the Above and Beyond Award from the Federation of BC Youth in Care Networks, the MOSAIC Human Rights Award, the United Way’s Excellence in Action for Early Childhood Development Award and was also nominated for a YWCA Women of Distinction Award in the community-building category, and an Award of Excellence from the Federation of Community Social Services.

Statuette Recipient Hon. Landon Pearson,O.C.

The Honourable Landon Pearson O.C. is a long-time advocate for the rights and well-being of children. From 1994 to 2005, Landon Pearson served in The Senate of Canada where she became known as the Children’s Senator as well as the Senator for Children. In May 1996, Senator Pearson was named Advisor on Children’s Rights to the Minister of Foreign Affairs. In 1998, she became the Personal Representative of the Prime Minister to the 2002 United Nations Special Session on Children. She then coordinated Canada’s response to the Special Session entitled A Canada Fit for Children.

Prior to her appointment to the Senate of Canada in 1994, she had extensive experience as a volunteer with a number of local, national and international organizations concerned with children. As Vice-Chairperson of the Canadian Commission for the International Year of the Child (1979), she edited the Commission’s report, For Canada’s Children: National Agenda for Action. From 1984 to 1990, she served as President and then Chair of the Canadian Council on Children and Youth. She was a founding member and Chai r of the Canadian Coal i t ion for the Rights of Chi ldren from 1989 unt i l she was summoned to the Senate.

Landon Pearson has publ i shed several books , including Chi ldren of Glasnos t , Let ters from Moscow, and the publ icat ion Tibacimowin (memor ies of the near past) . She has received many awards and honorary doctorates , was nominated for the Nobel Peace Pr ize for her work on behal f of chi ldren, and was appointed to the Order of Canada as an Of f icer for her work support ing the r ights of chi ldren and youth throughout Canada.

Her Honour Janet Austin, Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia

Conglaturatory Letter to Hon. Landon Pearson

Lillian Boraks-Nemetz Introducing Dr. Korczak: And His Flame Burns on

Janusz Korczak awards Presentation

October 18 2022

Dear Guests, a big welcome to our awards presentation event on behalf of the Janusz Korczak Association of Canada.

Firstly, since we are meeting virtually I wish to begin by acknowledging the indigenous lands that we are on, today.

My name is Lillian Boraks-Nemetz and I am your MC.

I would like to offer you some Reflections on Dr. Janusz Korczak, his heroism and its relevance to the 21st Century as seen through the Warsaw Ghetto Diary. Many years ago, when children were treated as beings to be seen but not heard Dr Janusz Korczak started fighting for their rights and became their champion. He had his own methodology which inspired the United Nations Charter of Children’s Rights.

Thus, he lit the flame on How to Love a Child one of his many books about children. And this flame still burns.

Korczak was and still is my hero.

On one of my early trips to Poland I made a pilgrimage to the Treblinka Death Camp where he and his 200 orphans perished.

Before I entered the camp, I saw a blown-up poster of Janusz Korczak attached to a hut at the entrance, but it is no longer there. The photo of this poster can be also found in the opening pages of his Ghetto Diary.

I stared into his eyes, mesmerized by their expression. If eyes alone can tell this grotesque story, his did. He looks out at the world with an expression of astonishment, shame and disgust. His eyes penetrate your soul with the same.

Small wonder.

I entered this stony museum of death reading inscriptions on the endless sea of stones….each depicting a lost Jewish community.

No graves of my family that perished there were to be found.

Only one stone had the inscription of a person: Janusz Korczak and children and the words-Never Again in German, French, English, Russian, Polish and other languages.

I ponder even now remembering these words- promises

That have not been exactly fulfilled. Were they?

The Treblinka experience had never left me. Just as Dr. Korczak stayed in my heart and mind.

I am humbly and indirectly connected with the sad and yet heroic

History of Korczak and the Warsaw Ghetto.

It is the children,” he wrote “who always had to carry the burden of history’s atrocities.”

Indeed. And they still do.

Korczak was also my father’s hero and it is from his stories that I found out what he stood for. Korczak and my father knew each other in the Ghetto. My father was a Jewish policeman who picked children up off the streets and found them shelter and food. He helped Korczak with food for his 200 orphans.

At this point, I would like to mention that what I have in common with Korczak is that my family and I were incarcerated in the Warsaw Ghetto at the same time. I a child, he and elderly man.

The streets of the ghetto reeked of garbage and bodies of men women and children dying from disease and starvation. People’s faces looked haunted by fear and deprivation. I saw this daily when my father took me to a secret school not far from where we lived. On one such day in the school we were drilled in case someone knocked on the door to put away our learning materials into a box on which we sat and only leave paper and crayons on the table. It happened one day that there was a sharp knock. We, children did as we were told and froze sitting our boxes. Two SS man the most dreaded of the Nazi army in black uniforms stomped in and started pushing our two lovely teachers around with the point of their revolvers yelling loudly in broken Polish, then stomped out. WE went home immediately. The next day when my father brought me to the school to my chagrin it was boarded up with words Schule Verboten…school forbidden. That day I and other children of the Ghetto lost their right to education just as we Jewish children lost our right to live. The janitor of the building ran out shouting that the teachers were send to Pawiak prison.

I was in tears because I loved the little school. That was when my father took me by the hand and we walked onto Dzielna Street where Korczak took care of the orphanage. A woman who was apparently an assistant to Korczak opened the door of a building which my father said was the Orphan’s Home. She knew my father and let us in. She told us that the Doctor was out getting food for the children. We sat down at tables strewn with books and papers. The children sat with us for a while then ran around behaving like normal children going about their daily lives seemingly oblivious to the outside Horror and stench. This place had an atmosphere of a world separate form the one we came from. It was Korczak’s world where where a sense of peace juxtapposed the chaos outside.

I got to know Korczak in the Ghetto through reading and re reading his ghetto diary.

Imagine the Old Doctor as he sits at night in a semi delapidated building on Dzielna street hungry and tired. A glass of vodka, a piece of black bread. Black out shades drawn and Korczak bending over his paper in the dim light of a kerosene lamp.

He will begin he says, by digging a well:

And I quote:

“I shall try to do something different with the story of my life Perhaps the idea is good perhaps it will work. Perhaps this is the right way.

When you dig a well you do not start at the deepest end. First you break up the upper layer, throw the earth aside shovelful after shovelful not knowing what is underneath, how many tangled roots, what other obstacles how many stones forgotten and buried by yourself and others….. Roll up your sleeves. A frim grip on the shovel…Let’s go…. This final work of mine, I must do alone.”

Korczak believed in honest discourse. Throughout the diary he talks to himself and sometimes to God, and he analyzes both the questions and the answers.

He wrote,

“You cannot even understand a child, until you achieve self-knowledge: you yourself are a child whom you must learn to know, rear, and above all enlighten.”

How many of us know ourselves that way?

Most of us have time to barely look deeply into our lives but judge ourselves and others by the last event at the top and never asking the questions, never shoveling to the bottom of the problem. Thus, coming up with erroneous conclusions and messages harmful both to ourselves and to those we judgeIn his diary Korczak reveals his most profound self which he uses as a blueprint for understanding the children.

As I sit and read Korczak’s Ghetto Diary, these words are constantly with me. For as I delve deeper and deeper into this candid and modest work I understand more and more the meaning behind those words. Korczak’s search for identity and his wanting to know himself and deeply understand his pupils, is the driving force behind all his work and especially the diary in his own words. In his diary Korczak writes that he learns about the children by observing them, their facial expression, meaning behind their words and their body language.

Their likes wants and dislikes. What they say, their stories and diaries. He wants to know what each child is in himself not as he should be in the eyes of society. The orphanage becomes Korczak’s laboratory and his diary the laboratory of his inner self, his child like imagination and his love for children.

Korczak reaches out of time deep into his mind, his soul: Into his childhood, his fantasies of another planet Ra of the good times in his youth, his parents the decrepitude of old age.

He writes his truth.

Like Viktor Frankl in Man’s search for meaning when he was incarcerated in a camp, thoughts and memories of good times food, and wellbeing kept him going as Korczak now sits at his desk tired, hungry and shabby remembering the delicious sausage, peace, comfort even luxury. At the same time, he is strong in his convictions that there is still beauty and goodness in the world…unlike Anne Frank in her diary.

But he requires something else…”Boredom,” he writes,” is the hunger of the spirit. Nostalgia -a thirst for water and for flight. For freedom. For counsel and an understanding ear to hear my lament.”

The diary goes on to reveal his truth. Unlike many memoirs who foil the truth by showing off their heroism and who they know.

“A man of today has matured,” Writes Korczak, “But he has not become wiser or gentler. “

He writes about his first realization, the dichotomy of his religious identity:

He considered himself a Pole and a Jew but was conflicted when at the age of 5 his canary died and he put it in a box and wanted to bury it putting a cross on top of the grave.

Korczak writes “The housemaid said no because it was only a bird, something much lower than man even to cry over it was a sin. What’s worse the janitor’s son decides that canary was Jewish and so was I. I, too was a Jew, and he a Pole, a Catholic. It was certain paradise for him but not for me. I would end up when I died in a place which though not hell, was nevertheless dark and I was scared.

Of a dark room, Death-Jew -Hell. A black Jewish paradise. Certainly, plenty to think about. Korczak admits later on that his father and uncle worked hard to bridge the gap between Christians and Jews.

At this point I would like to read you a poem Korczak wrote in 1920 expressing his wish. I translated this poem into English in September 2009.

A Teacher’s Prayer

Although grey and humble in your presence, Lord,

I stand before you consumed with longing.

Whispering quietly,

I state my wish in a voice of unfaltering will.

My eyes fire a plea beyond the clouds.

Standing tall I ask not for myself,

Please, endow the children with good will,

Offer them help in their efforts,

Give their toil your blessing.

Lead them along a path that is not the easiest

But most excellent.

The poem speaks to me. I came to Canada and my life was not an easy path but it was an enlightening one for though hardship I learned independence.

I remember when we child survivors came here to Canada and there was no understanding ear, or interest in our immediate past and that was when I learned from someone like Korczak that not through avoidance of the past but through facing it and dealing with it could I ever free myself from the shackles of a terrible memory.

The diary runs like an hour glass of Korczak’s life and thought like the well that he digs till the spade reaches the bottom. Through the process of reading I gain more and more respect for this man’s thoughts and more and understanding how this struggling human being exercises his will when at the end of his rope to keep the children’s morale and his own alive. It takes a big big heart with a will of gargantuan strength.

The phenomenal point of the diary is that never the word Holocaust or genocide is mentioned and rarely the Ghetto. Yet you feel the oppressive sliminess of the outside world creeping slowly into the home, towards a tragic denouement.

Korczak describes the following:

“The children moon about. Only the outer appearances are normal. Underneath lurks weariness, discouragement, anger, mistrust resentment and longing. The seriousness of their own diaries hurts. In response to their confidences I share mine with them as an equal.

Our common experiences, theirs and mine. Mine are more diluted, watered down, otherwise the same.”

Korczak also wrote the following:

“What a tragedy is our contemporary life and how shameful of this generation to be passing onto its children a chaotic world. “

This observation made by Korczak years ago is still so relevant in the 21st century for what has changed?

And Korczak is still with us today.

In a world where children are still in war zones hungry and without shelter. But thankfully today we know what we must do to fight for the welfare of children.

Marcia Talmage Schneider titled her recent book so aptly, Janusz Korczak – Sculptor of Children’s Souls.

And we so many years later we’ll follow his example.

So that the flame may continue to burn on.